When I was younger, I would read magazines and look at all the beautiful expensive things in them, and I would wonder why I couldn’t seem to find things like that in the real world. Every August, I would stand in the stationery aisle at Target and look at the erasers and the rulers and the pencil boxes and something about the candy colors and the gloss of the shrink wrap seemed to promise the same things that the magazines did. In Mervyn’s and Gottschalks, there was always an aisle far from the registers where the ambient sound was muffled by the clothes on the hangers, and the surrounding patterns and textiles could be anything, if you unfocused your eyes.

But whenever I plucked one of those things from the shelf, the spell was broken. The colors, removed from context, were wrong in ways I couldn’t quite articulate. (They were the cheap colors, chosen for mass appeal.) The lids of the pencil boxes never lined up properly with their bottom halves. Everything, even the erasers, had seams, and those seams were always ragged and scratchy. The manufacturers wanted you to fall in love at the shelf, and they hoped that love would last through checkout. But, once you left the store, they no longer cared what you thought. The object had nothing more to show you, except, possibly, the surprising and novel ways that it would immediately begin to deteriorate.

It’s by no means impossible to find well-made, high-quality things in this world. You just have to pay a premium for them. When I moved to New York, I found the stores that actually sold the same expensive things that the magazines advertised. The colors were always interesting and original, and the seams were always neat and unobtrusive. They had unexpected little compartments and convenient features that promised to reveal themselves gradually, as you spent more time using it. When I saw these things and held them in my hands, I could tell that I could love and appreciate them forever, or at least until the end of the season. I never found out which, because I couldn’t really afford to buy them.

Eventually, I realized that you could get better, more unique items without paying an extreme markup. You just had to buy vintage. And, if you bought broken vintage, you could pay almost nothing. Of course, the thing was also worth nothing, unless you could fix it. But Jon and I had google, we had tubebooks.org, and we had a dream (having a studio stuffed with cool vintage gear).

We started buying Wurlitzers because they were cheap, compared to other vintage instruments on the market. They were gross, usually: dusty, broken, and covered in grime. At first, I didn’t think too much of them. In their poor condition, they reminded me of anything you could buy at the average store: decent in concept, but disappointing in execution.

The third or fourth Wurlitzer we bought was a 140b. It was dirt cheap because the amp didn’t work. We didn’t really know how to fix amps, but we had achieved success in the past by swapping tubes, polishing tarnished RCA jacks, and double-checking that all necessary inputs were plugged in. Unfortunately, after checking all the simple fixes, we realized that the electronics were truly broken. In other words, the keyboard was a doorstop.

The Wurlitzer reed bar requires a polarizing voltage, similar to the way a microphone requires phantom power, so it would not be possible to bypass the onboard amp and use an external one. At the time, nobody was making replacement 140b amps, so installing a new one was not an option. Our usual amp tech was not willing to touch anything that used germanium transistors. We contacted repair people, but they either had no ideas, or offered opaque solutions that were entirely out of our budget.

Lacking other ideas, I googled the problem and found multiple forum threads about the Wurlitzer 140b. There, the consensus seemed to be that the keyboard is essentially worthless. It was an older, junkier version of the 200a, and therefore had very little resale value. It was unreliable and unfixable. It was silly to buy one, and even sillier to spend time trying to make it work.

There are smart, knowledgeable people who post on forums, but, like anywhere on the internet, negative and pessimistic content often gets more engagement. And so, if you ask a question on a forum, you’ll get a handful of well-meaning people trying to help you solve whatever your problem is. But you’re also likely to get a reply from someone who thinks your gear is trash, that it should be thrown out or sold to the lowest bidder, and that you should buy XYZ alternative piece of gear instead. (The gear suggestion is always random and, likely, something the poster overpaid for and wishes other people would take an interest in, hopefully stimulating its resale market.) And, people will entertain that suggestion, because for some reason there is more gravitas in discarding an object than in trying to make it work again.

Here’s a paradox: a musical instrument might last 50 or 70 years, changing hands multiple times, surviving extremes of temperature and humidity, retaining much of its functionality, and, by doing so, essentially proving its longevity and desirableness. However, if the instrument shows any evidence of that passage of time—if it’s not 100% functional, or if some of its sounds are kind of “cheesy,” or if it doesn’t link up seamlessly with digital gear unveiled at NAMM last year—that is considered evidence that the instrument has no longevity, and that it should be discarded. We’re all so accustomed to single-use plastic garbage that we start to assume that everything is manufactured along that model.

BACK TO THE BROKEN 140B

And so, we had this broken Wurlitzer 140b that apparently could not be fixed and did not seem to have very much value. We could have, justifiably, thrown it away, and focused instead of acquiring the “better” models of electronic piano. This would have been a very efficient use of our time and our resources.

But although the piano was broken and quickly becoming a sinkhole of time and energy, we loved it. And the more time we spent with it, the more things we found to love about it. Wurlitzers have so many little design details that are not just beautiful individually, but contribute to the shape and function of the keyboard as a whole. As a mass-produced item, the 140b’s design was intended to appeal to a wide range of people, but its makers weren’t afraid to give it a little character. The paint is a cool beige that leans mauve, with white speckles. The rounded opening where the speaker mounts is repeated in the openings for the rear amplifier controls. The screws and washers are gold to match the leg hardware. And—my favorite part—the legs can be disassembled into a single box, completely enclosed and easy to move from place to place.

The mechanical design of the keyboard is also beautiful. All of its moving parts are open and accessible and intended to be repaired and periodically adjusted. It’s not the kind of thing that you have to cart to the dumpster if something goes awry. It’s true that nobody seemed to know how to fix the 140b’s amplifier, but that’s not because it was poorly made. In fact, the amplifier has a very straightforward layout that invites repair. The problem was simply that the old solid state components had been discontinued long ago, and popular knowledge about how they work had faded with time.

The sum of all these details gave me the impression that the manufacturer actually wanted the user to not just purchase the keyboard, but to actually enjoy using it once they brought it home. And why? The Wurlitzer is not a subscription service. It doesn’t have endless add-on accessories. The customer buys the keyboard once, and has no further obligations to the seller. Theoretically, the customer could develop loyalty to the company, and eventually buy more Wurlitzer instruments, but even that is becoming an old-fashioned business model.

So, the keyboard was broken, but, simply by designing with the possibility of repair in mind, the manufacturer had met us halfway. The longer I spent with it, the more I noticed the little details that made it special. Sixty years before, someone had put thought and care into its design, assuming that whoever acquired it would want to maintain its working condition. I was willing to put the effort into making it work again. Eventually, I did. After several months researching and tinkering (and troubleshooting more complex problems than disconnected input cables), I became more confident in my ability to repair vintage amplifiers. I did this, not because I had any special background in electronics, but because I appreciated the keyboard and its sound and all of the small details that make it unique. Because Wurlitzer took so much care in those details, the keyboard still holds up today, even in an age when so much cool and unique tone is available digitally.

WURLY DETAILS & THE DOCUMENTS

Visiting the Wurlitzer warehouse last fall, where we had one final opportunity to purchase original spare parts for Wurlitzer keyboards, was an intense experience. Jon and I had just driven sixteen hours, we were working with a pretty small budget, and we only had a couple of days to look through hundreds of boxes of old parts. We had unfinished projects waiting for us at home, many with deadlines that were becoming rapidly overdue. We felt a lot of pressure to find and salvage all of the parts that were useful for electronic pianos. But, even as we browsed, a cleaning crew was throwing things away and destroying paper and cardboard.

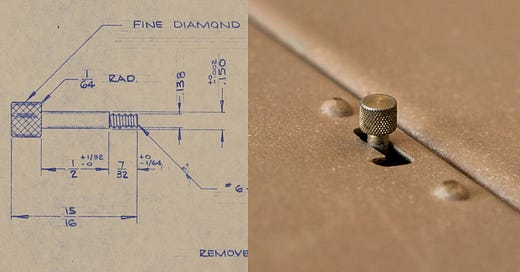

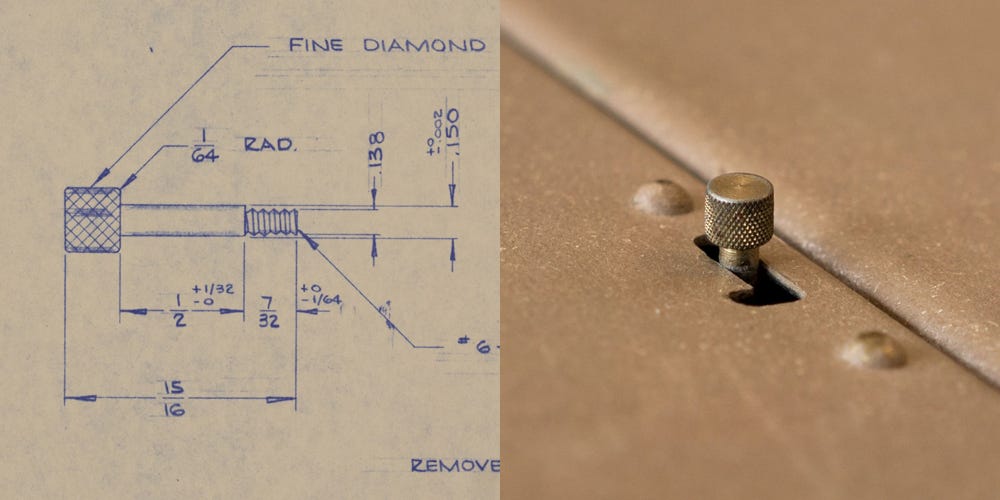

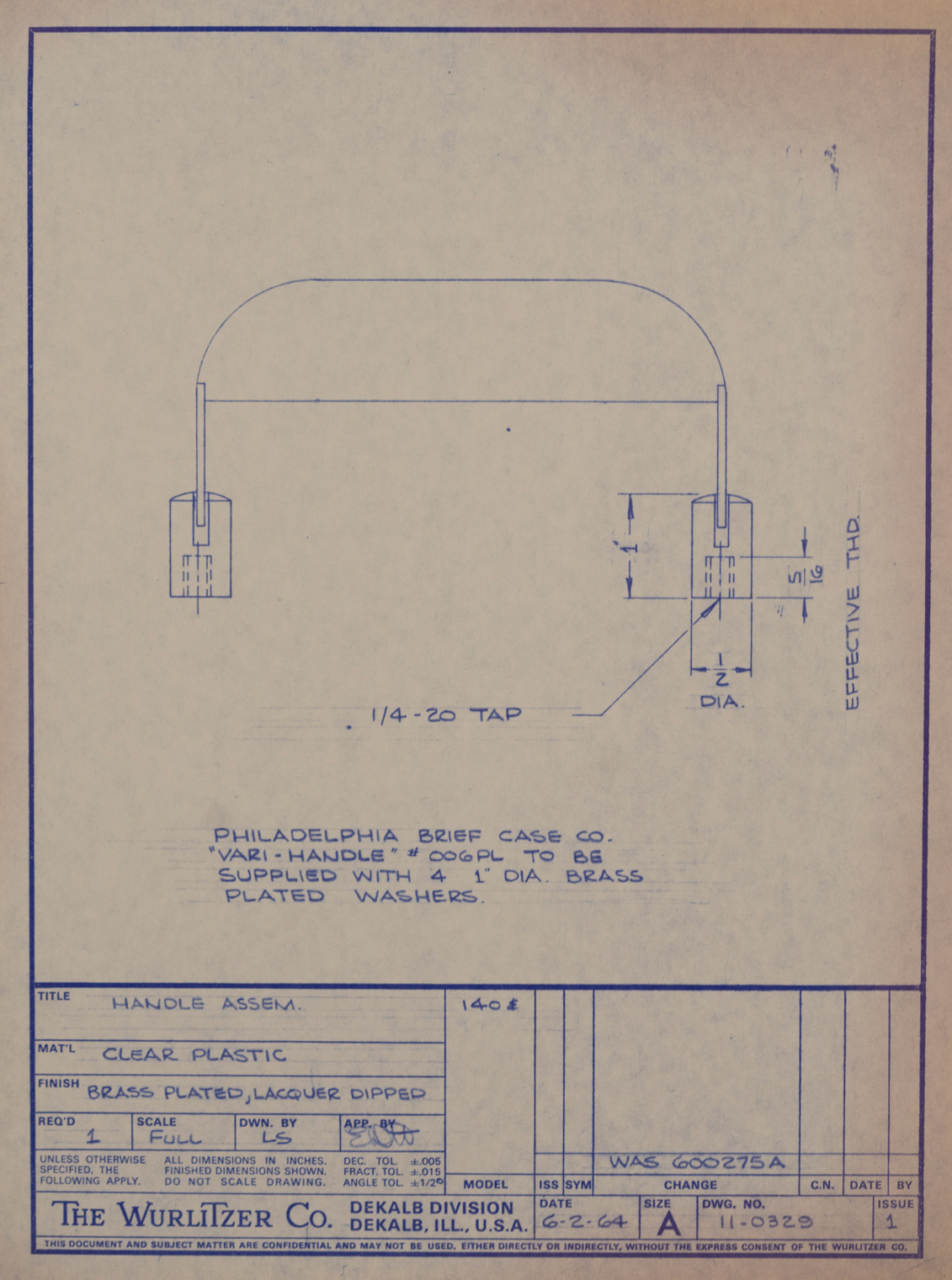

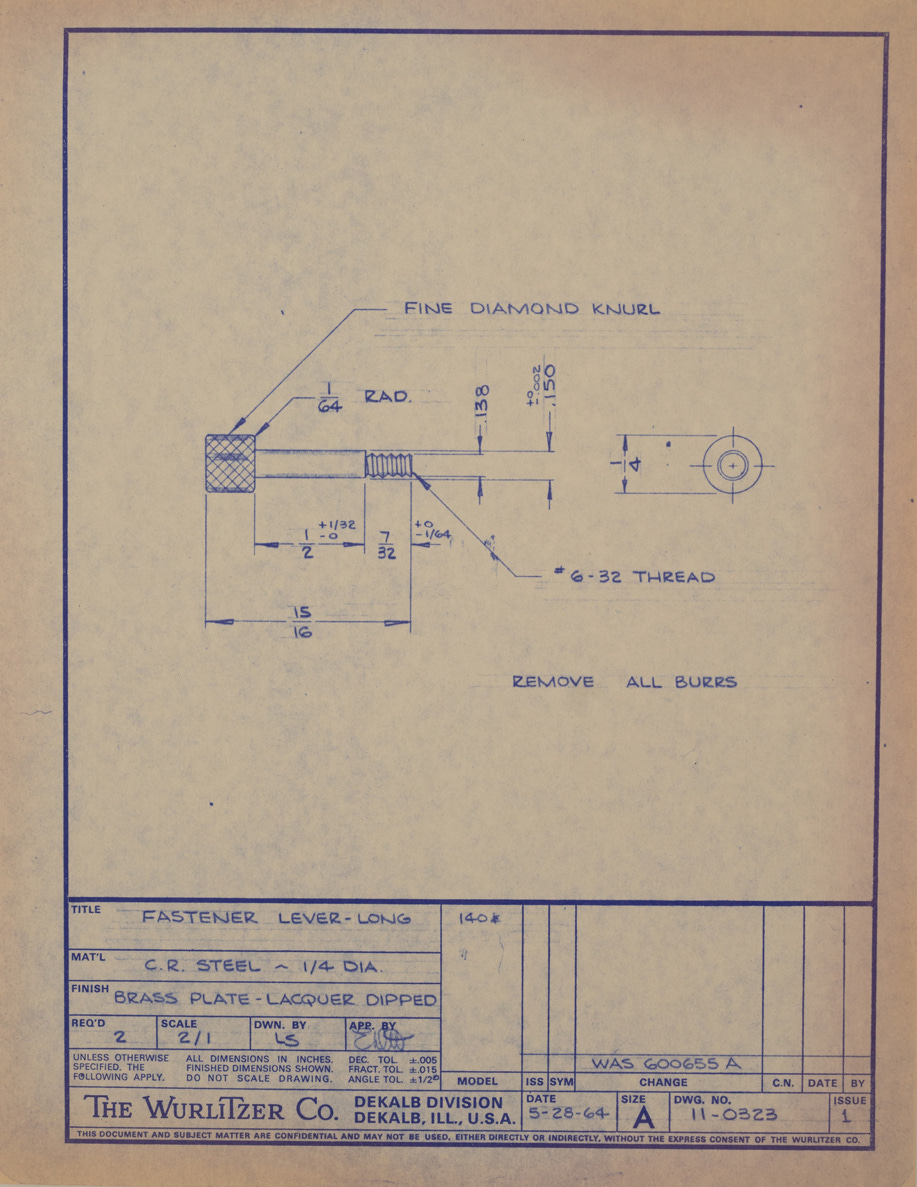

Right before we left the warehouse, Jon opened a filing cabinet and showed me a drawer overstuffed with blueprints. Each blueprint depicted one part from a Wurlitzer keyboard: an amplifier chassis, a piano leg, a tee nut, a screw—all of those little details that make Wurlitzers special, drawn in ink. Some blueprints had additional paperwork that described difficulties in the manufacturing process, and the steps the engineers took to mitigate those issues and keep production moving forward. These were stories that, before we knew about the documents, were simply speculation.

In total, there were thirteen filing cabinets, and thousands of drawings. But we had exhausted our budget, and we couldn’t imagine how we could transport that much paperwork back to New York. So we left. We drove for seven hours straight. But the more miles we put between us and the warehouse, the more we realized that we had to go back for the drawings. And we did.

For me, the documents make the Wurlitzers that much more real. It seems obvious that someone designed, built, and sold these keyboards—that every step in its creation was made possible by the work of real people. But, with the Wurlitzer Co. defunct for so many decades, the human element starts to get a little abstract. When you pull a Wurlitzer from the depths of an old storage shed, after the dust has given it the color and texture of its surroundings, you could almost mistake it for a relic of the earth itself. The documents prove that the truth is a little more mundane.

And yet there’s a different kind of magic in holding an original Wurlitzer part beside the engineering drawing that depicts it. Time starts to collapse. There’s fifty or sixty years between today and the day the drawing was printed, but we’re still doing the same task. We’re making the keyboard work, and we want the person who plays it to have a good time.

This is all to say that we’ve finalized our lighting setup, and we’re ready to scan more 8.5"x11” drawings. I can’t wait to show them to you!