Saving and scanning the Wurlitzer documents

Why and how we ended up with thousands of Wurlitzer Co. engineering drawings

Last month, we went to a warehouse that had a lot of Wurlitzer electronic piano and organ parts. For decades, the warehouse was owned by a former employee of the Wurlitzer Co., but he sold it earlier this year, and the new owners wanted everything gone. There’s a lot more to this story—but, in short, we visited the warehouse and ultimately purchased thirteen file cabinets of Wurlitzer Co. engineering drawings.

We were able to purchase these drawings thanks to the generosity of our friends and the Wurlitzer community. We didn’t go to the warehouse for clever business reasons, or because we have any kind of sensible savings account that we can dip into anytime we hear about a great sale. We went because we suspected that it contained things that would be lost forever if we didn’t go down and buy them—in particular, the little screws and plastic pieces that you only notice when they’re gone, and you have to replace them with something new, ill-fitting and cheap-looking. We could afford our little parts (we hoped), plus gas for the trip, as long as we kept it brief and stuck to the essentials.

The thirteen file cabinets did not seem like essentials, so we left them. (At least, they didn’t seem any more or less essential than any of the other cool, irreplaceable stuff at the warehouse that we had to leave behind because we ran out of money.) We drove halfway home (seven hours). But we couldn’t stop thinking about the documents.

We called our friend Steve and told him about the documents. The more we described them, the less defensible it seemed to leave them behind. Steve thought the documents were important—we did too, but, back at the warehouse, surrounded by all these impossible NOS Wurlitzer parts, we couldn’t help but wonder if we were just being sentimental. But Steve hadn’t been to the warehouse, and we felt that gave him a more objective perspective.

We were also getting DMs about the documents—all kinds of comments, but mostly questions about what would happen to them. I told everyone that they would be burned, which was the truth. It was also a depressing thing to put into words. Most people were incredulous. Do they need to be destroyed? Surely someone would want to save them? Yes, but it was 10 PM on a Sunday night, and the warehouse’s new owners had a cleaning crew coming at 8 AM the following morning. This isn’t how I would personally handle the situation, if I had thirteen file cabinets of drawings that I didn’t want. But, of course, it wasn’t my warehouse and it wasn’t my decision.

Steve suggested contacting archives and urging them to acquire the documents before they could be destroyed. (The Smithsonian has a collection of Wurlitzer papers, which helps make the case that the drawings aren’t just random ephemera, but actually have historical value.) I thought this was a good idea, but I wondered whether an archive could mobilize fast enough. I imagined an institution expressing positive interest within a sensible period of 5–7 business days, just so that we could call the warehouse owners and find out that the documents had been destroyed hours or days earlier. This was a rollercoaster of emotions that we didn’t really want.

Nobody criticized our decision to leave the documents behind. Everyone understood that rescuing them was a big project, that we had stuff to do back home, that we didn’t have any particular duty to save thousands of pounds of paper, the existence of which we only learned about about 24 hours before. But every suggestion we heard, every potential solution, only made us realize that we—of all people on earth—were in the best position to acquire the documents. We knew where they were, we didn’t need to be convinced that they had historical value, and we were already on the road. We could just turn around and get them. Of course, we didn’t have the money to buy them, we didn’t have the means to pack them up and get them to New York, and we didn’t have the time to spend on any of this. We had other obligations, other things we have to prioritize to keep the lights on, to put food on the table. I mean this literally. Driving home was faultlessly sensible. It also felt really shitty.

I woke up at 5:30 the next morning thinking about the documents. Jon and I cycled through some harebrained schemes before we truly came to terms with the idea of turning around and picking them up. We couldn’t do it without help—but the community came through, something that we are grateful for.

It took us days to pack up the documents, and then repack them into a storage unit. All in, we spent two weeks on the road. We had originally budgeted five days for the trip. Back in New York, we are still catching up on the work we have to do. But saving the documents was worth it.

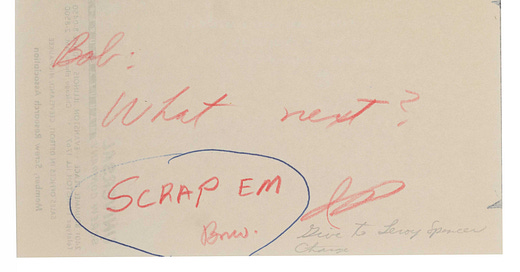

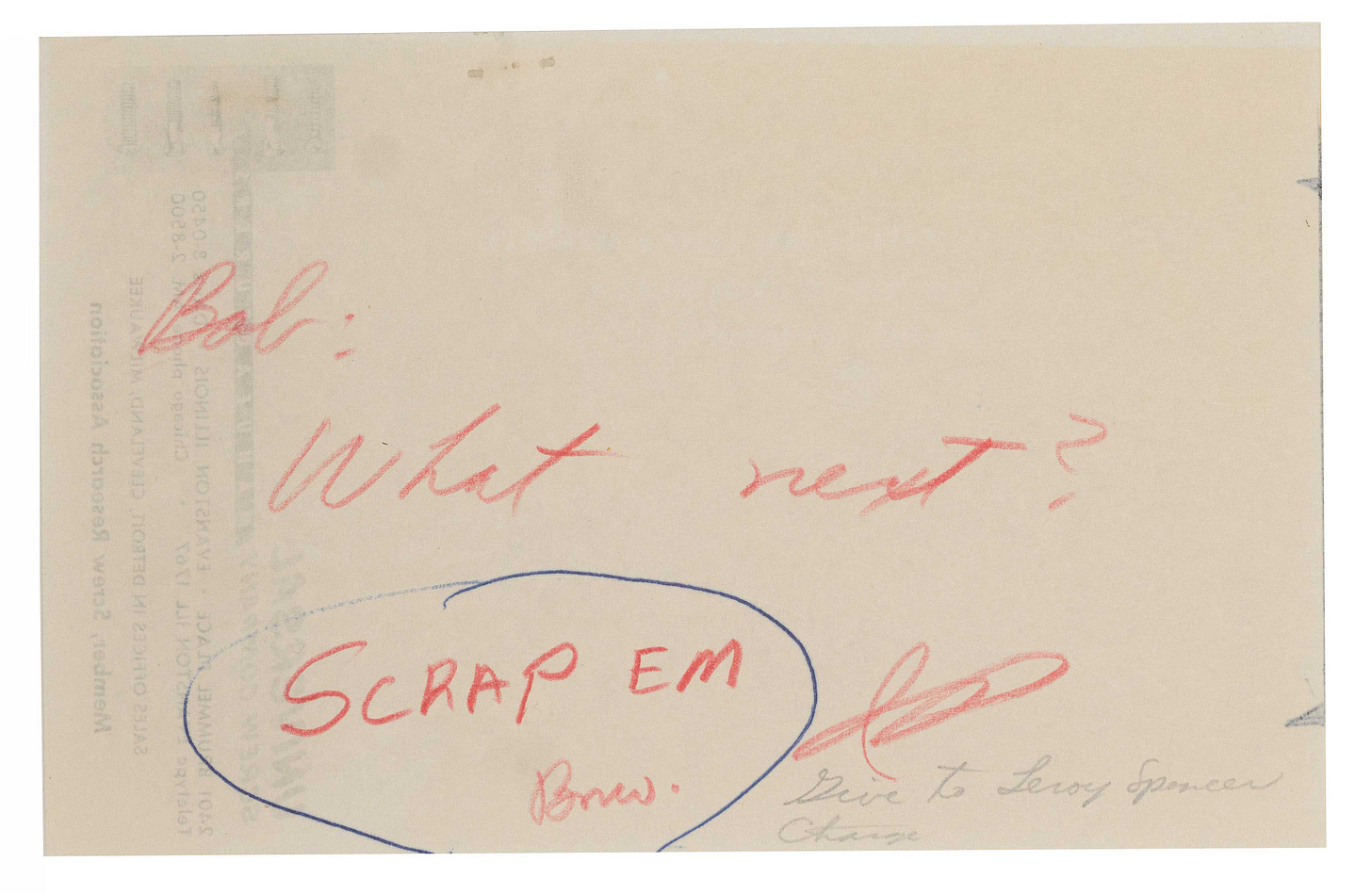

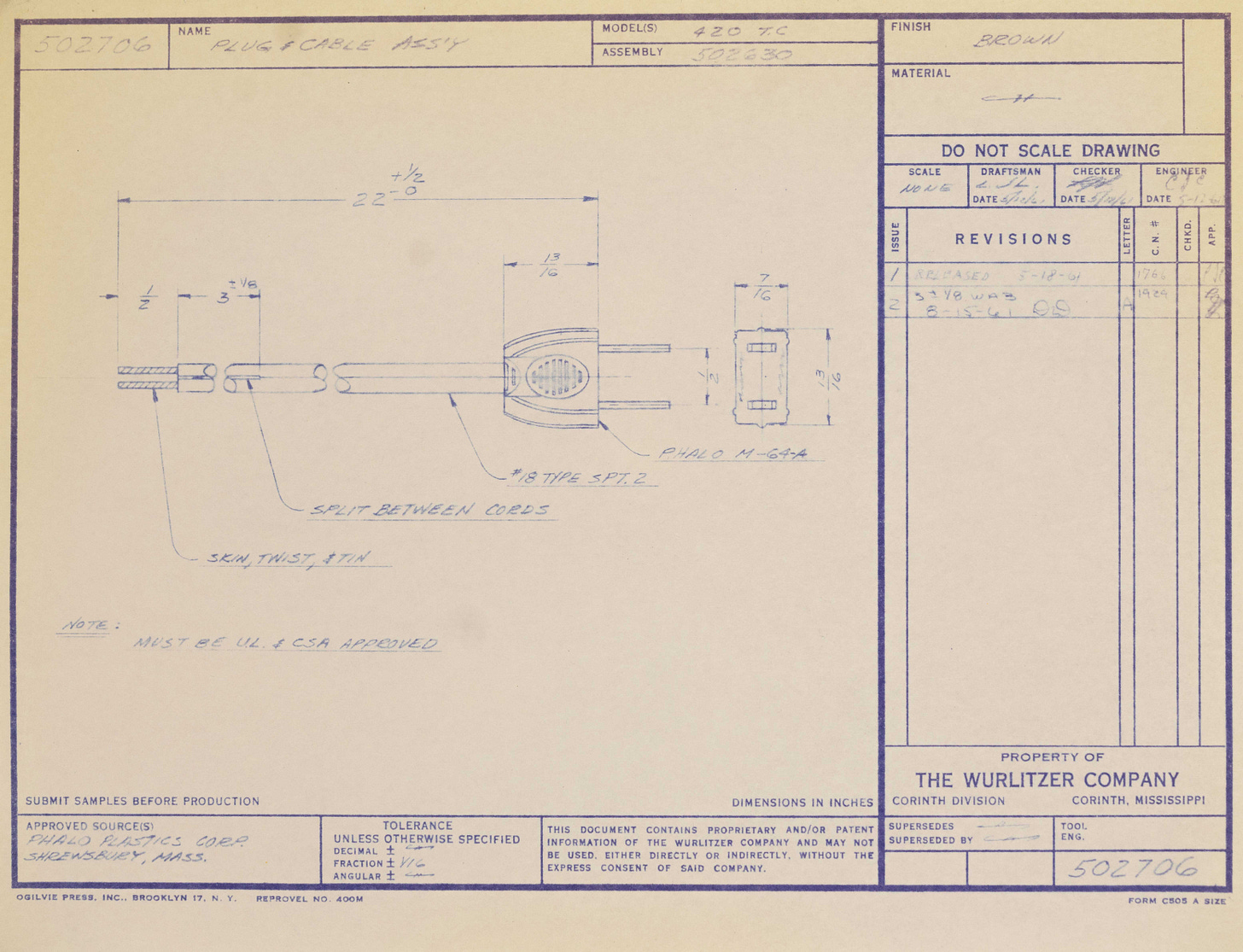

We fit as many documents as we could in our car—about 1200 drawings, plus the supporting paperwork that is often included in the file. Some of the individual drawings offer a lot of important insights: transformer specs, details of materials, measurements. Some drawings are in folders that include correspondence between the Wurlitzer factory and the parts manufacturer, mostly when things went wrong and the factory rejected a delivery for whatever reason. The dynamic between the Wurlitzer Company and its vendors is very interesting. Some vendors wrote humble apologies promising to fix errors in future shipments. Other vendors had a take-it-or-leave-it attitude. At one point, RCA refused to accept a return of defective 7868 tubes. “What next?” asks a handwritten note included in the file. Written just below that: “SCRAP EM.”

The next step is to bring the rest of the documents to New York. The bulk of them—what we couldn’t fit in the car—is currently in storage. In New York, we can digitize them, and make them available for people to read them and learn from them. These documents are a window into the Wurlitzer Co.—and probably 1960s and 1970s manufacturing in general—that doesn’t exist anywhere else.

If you’d like to help with this project, please consider donating or sharing our fundraiser.

And thank you for subscribing to Keyboard Notes! It’s been a chaotic couple of weeks, but I’m happy to be back writing newsletters. Coming up soon: details on a new method for whitening keys, plus I’ll share some highlights from the documents so far (including a drawing that solves a minor mystery!!).